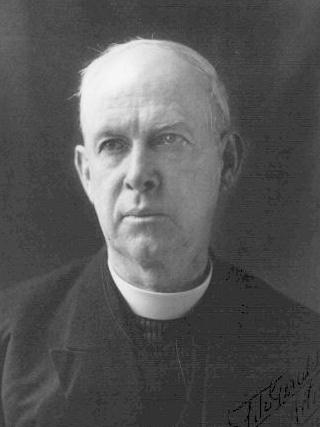

Father Zahm

by John Cavanaugh, C.S.C.The Catholic World, February, 1922.

WHEN Father John Augustine Zahm, C.S.C., passed away in Munich,

Bavaria, early in the morning of November 10th, his friends felt that

his death was premature despite his Scriptural three score years and

ten. Wise men say that stature and longevity are among the qualities

most surely inherited, and Father Zahm came of a long-lived family. He

once told me of a grandfather of his who died at the age of one hundred

and five under interesting conditions. He had walked fasting to church

one Sunday morning, according to his custom, received Holy Communion,

and then walked home. While waiting for breakfast, he lay down as usual

on a sofa to rest, and when they came to call him shortly afterwards,

they found he had passed away without sound or sign. It is probable

that Father Zahm, under ordinary circumstances, would have lived into

venerable years for, though his life was the most laborious I have ever

known, it was also extremely abstemious and regular. But years ago his

heart had been strained by physical over-exertion, and when pneumonia

attacked him, he had not the machinery with which to fight back.

WHEN Father John Augustine Zahm, C.S.C., passed away in Munich,

Bavaria, early in the morning of November 10th, his friends felt that

his death was premature despite his Scriptural three score years and

ten. Wise men say that stature and longevity are among the qualities

most surely inherited, and Father Zahm came of a long-lived family. He

once told me of a grandfather of his who died at the age of one hundred

and five under interesting conditions. He had walked fasting to church

one Sunday morning, according to his custom, received Holy Communion,

and then walked home. While waiting for breakfast, he lay down as usual

on a sofa to rest, and when they came to call him shortly afterwards,

they found he had passed away without sound or sign. It is probable

that Father Zahm, under ordinary circumstances, would have lived into

venerable years for, though his life was the most laborious I have ever

known, it was also extremely abstemious and regular. But years ago his

heart had been strained by physical over-exertion, and when pneumonia

attacked him, he had not the machinery with which to fight back.

Piety was another inheritance of his. The Zahms came from Alsace and were of the German rather than the French flavor among that mixed people. Rugged faith, hardy character, dogged persistence, honest thrift, were their characteristics. His mother, Mary Ellen Braddock, came of the same stock as General Braddock, famous in early history in America. She was of strong Irish quality -- pious, intelligent, beautiful, idealistic. I have often noted that the children of mixed German and Irish parentage have more than their fair share of mental and moral power. An aunt of Father Zahm's was a distinguished Superior among the Sisters of the Holy Cross, and three of his sisters became members of the same community. One died a few years ago in heroic sanctity. A brother, Dr. Albert F. Zahm, is chief advisor to the United States Government in aviation, and had a large part -- if not the very largest part after the Wright brothers -- in the invention of the aeroplane.

Father Zahm was born in the village of New Lexington, Perry Co., Ohio, June 14, 1851. Among his boyhood friends was Januarius Aloysius McGahan, the most distinguished newspaper correspondent of his time, whose revelations of the Bulgarian atrocities stirred the wrath and eloquence of Gladstone and awoke the conscience of the world. McGahan and Zahm sat on the same bench in the little log school, where began the preparation for their distinguished careers. When Father Zahm came to Notre Dame to begin his college work in 1867, the venerable founder, Father Sorin, was Provincial Superior (next year to be elected Superior General), and the famous war chaplain, Father Corby, was President. The records show that John Zahm was exceptionally studious and successful, and he graduated with honors in 1871. Shortly after he entered the Novitiate of the Congregation of the Holy Cross, and at the end of the usual theological studies was ordained in 1875, Father D. E. Hudson, C.S.C., for nearly half a century editor of the Ave Maria, being the only other member of the class. It was an auspicious day that gave to the young community and to the Church in America two such brilliant and zealous priests.

Father Zahm's earliest tastes were distinctly for literature, and he had pursued the course in arts and letters; but there was need of a science teacher in the University of Notre Dame, and following the general and seemingly necessary way of that time, his superiors appointed the young priest Professor of Chemistry and Physics. The work was distasteful and his preparation for it had been only ordinary, but without demurring Father Zahm stepped into the breach. Undoubtedly neither he nor his superiors realized that upon that moment of necessity hung a decision that was to mean much to the Catholic Church, especially in our country. As time went on, he had to master and, occasionally, to teach geology and other sciences. Thus was providentially prepared the background for his future work. One great technical work came out of his laboratory experiments during his teaching days, the exhaustive text on Sound and Music, since used as a book of reference in many State universities.

Even in his seminarian days, he had given public lectures, and as a young professor he frequently published substantial and readable papers on interesting aspects of science or travel. These papers, while scholarly and valuable, were not distinguished in expression. He had not yet developed a personal style.

About the time his powers were maturing, the world was almost mad with tumultuous and angry discussion. Darwin had started the strife by his revolutionary doctrines concerning evolution. Many men of science outside of the Church had little or no Christian faith to give up, and all of them welcomed what seemed an exploding bomb in the camp of those whom they called obscurantists and reactionaries. Brilliant expositors of the new doctrine arose on all sides, the most distinguished being Huxley and Tyndall. Herbert Spencer, by an effort of genius, almost equal to Kant's, built up a philosophic system in defence of it, only to find that when his gigantic work was concluded after many years, the world had very largely abandoned his fundamental principles.

Needless to say, both the sacrilegious delight of the scientists and the alarm felt by timid Christians were equally without foundation. As the truism universally adopted at the time expressed it, God is equally the author of scientific and revealed truth, and there can be no contradiction between science and religion, both rightly understood. It is a fact that some religious writers had pushed the outposts of Faith very much farther than Catholic doctrine demanded or justified -- a very natural outcome of the state of general knowledge then and theretofore. On the other hand, the scientists, bewildered by what seemed a fresh vision of universal principles, and intoxicated by the rich liquor of partisanship and controversy, had undoubtedly advanced the outposts of science to absurd lengths. Between these extremists lay the field of battle, No Man's Land. There were sturdy champions on the side of Christianity, men of prodigious learning and giant intellect, but their path was not easy; it took time to clear the atmosphere and evaluate data and strip principles bare; and meantime the merry war went on.

Into this situation Father Zahm stepped at a curiously felicitous moment. The best men on the side of the iconoclasts had began to lose the zest of attack and slaughter. Moreover, they themselves were beginning to see that in their mad fury against dogma and traditionalism, they had set up an intolerable dogmatism of their own. At the same time the theologians were acquiring poise, had emerged from their first confusion and were beginning to reply vigorously with their big guns.

Father Zahm's general background of scientific preparation, together with his theological training and his taste for literary expression made him an ideal protagonist of faith. His earliest essays as a Catholic apologist were contributions to the Ave Maria and the American Catholic Quarterly and to The Catholic World, and had for their general thesis the harmony between what he called "the sciences of faith and the sciences of reason." Only a quarter of a century has passed since that time, and anyone who should now write on the subject would be tolerantly regarded as an old-fashioned gentleman employed in executing a corpse. But it was a lively corpse in the days when Andrew D. White, a man of reputation and nimble mind, a distinguished diplomat and President of Cornell, was writing interminably on The Warfare Between Religion and Science, and when J. W. Draper was producing his popular History of the Conflict Between Science and Religion. Besides establishing his thesis, these early brochures{1} of Father Zahm's bristled with valuable and interesting facts about Catholic men of science of the past, and constituted a magazine of ammunition for busy controversialists. Of the same tenor and quality was an impressive volume (1893) entitled, Catholic Science and Catholic Scientists, except that problems were beginning to assume more importance in his work and persons less. This volume, though much surpassed by the quality of his later work, is still of value and importance.

Up to this point, Father Zahm had a united Catholic backing to support him. As long as he stayed within the old fortresses and ventured not into fresh battlefields nor used strange weapons, he enjoyed not only a growing fame among the faithful, but the marked approval of all Catholic scholars as well. But at this time there sprung up in our country the interesting movement which produced the still vigorous Catholic Summer School at Plattsburg, the Western Catholic Summer School (now defunct) at Madison, Wisconsin, and the Catholic Winter School (never vigorous) at New Orleans. At all of these Father Zahm was invited to lecture, and he somewhat audaciously chose for his subject the most difficult, delicate and dangerous topics a Catholic apologist could elect. There can be no doubt about his honesty, his zeal or his lofty motives in selecting these themes. His ruling passion in all his priestly work was an intense zeal for the glory of God and the triumph of the Church. He felt that too many Catholic scholars in defending the Church had displayed a timidity which seemed almost to argue feebleness of faith. He found, as he went into the work of the old theologians and apologists, and especially the broad and profound writings of the great Fathers of the Church, a sweep, a power and a liberty which seemed equally necessary to establish in their full strength the truths of Christianity in our day. The problems he attacked had, through newspapers and magazines as well as books, sifted into the general consciousness, so that he felt sure an audience like that of a summer school would be both interested and intelligent enough to receive his message. The newspapers played up his lectures somewhat sensationally, with the good result that everybody read them, and talked about them; and without doubt many who considered the Church as obsolete as pagan mythology, were constrained to revise their views, while Catholics generally felt that a new and lusty champion had entered the lists for them.

A result not so good was that certain Catholic scholars took alarm, and felt that the Church might need a defender against some of her defenders. Father Zahm immediately became a storm-centre of controversy within the Church; one influential and brilliant party attacking him with spirit, while another, not so large, but probably more brilliant, as ardently defended him. The volume which contains the earliest of these lectures is entitled, Bible, Science and Faith, and deals with such problems as the days of Genesis, the universality of the deluge and the age of the human race. That volume still remains the best statement on these subjects in English from a Catholic scholar. Of the same period is Scientific Theory and Catholic Doctrine, which focused itself more particularly on the subject of evolution, the head and front of the phalanx of scientific difficulties. Father Zahm was evidently crystallizing into the mental attitude which was soon to produce the greatest of his apologetic works, the climax of this period of his life, Evolution and Dogma.

It required the courage of a superman for a priest to attack this question with the plainness and freedom of the ancient Fathers. Theology has become a highly organized science since their time, and there is a natural tendency in any ancient human thing to mistake ruts for roots and prejudices for principles. One considerable group of learned and well-meaning men was sure to be affronted by the boldness of this modern knight. More than that. Those who think theologians are a pacific, esoteric, compact and always harmonious group of thinkers know little of the tribe. That would be true if the Church were what some of her critics proclaim her to be, a purely human institution, dealing in quackery and deception, and with an astute and avaricious priesthood profiting by the credulity of the faithful. But the passion of the Catholic theologian is for truth. And he is seemingly just as delighted to catch a fellow-theologian napping, in order that he may -- especially if he belongs to a different religious Order -- acquire heavenly merit and perform an act of fraternal charity by giving a brotherly correction in clear and vigorous terms, as a football player is to recover the ball when his adversary fumbles it. If people only understood the vigilance theologians have exercised against each other through all the centuries from the earliest days of the Church, there would be less talk about innovations of doctrine and accretions and corruption of primitive Christianity. Father Zahm's position regarding evolution was clearly within the limits of regular Christian hermeneutics. He was as far from the materialistic theories associated with the modern anti-Christian movement as the drowsiest or most inquisitorial of his critics. But the controversy soon passed beyond the limits of America. His works were translated into French, Italian and Spanish, and he was as widely read in Europe and South America as he was in the United States. Non-Catholic scholars wrote of them in magazines and heterodox divines discussed them in university lectures. Controversy waxed furious and sometimes frenzied. One great Catholic publicist of international repute and of terrible -- that is just the right word -- influence in Rome, wrote a series of articles, proving to his own satisfaction that Father Zahm was an "atheist, a Materialist and a Modernist." Meantime, the gentle priest, whose heroic militancy for Christ was the cause of all this clamor, remained placid and pacific among his books. He knew how high was his purpose, how pure his intentions, and he was content to leave the result to the infallible arbiter of Faith. Beyond doubt, there was a large and clamorous party demanding that Evolution and Dogma should be placed on the Index. It was a close call, but it was never placed there;{2} and Father Zahm had the serene satisfaction before his life closed of finding the views he so courageously and clearly defended, accepted as the commonplaces of Catholic controversy by many of the same school of apologists who hurled theological brickbats at his devoted head a quarter century ago.

Most of us who knew Father Zahm intimately, believed that he had prophetic instincts. He was a real seer, and people who see, always look ahead. Among other enthusiasms of his from his youth was a burning zeal for the higher education of women. He did more than his share locally at Notre Dame to promote it, and with voice and pen labored incessantly to arouse a similar enthusiasm in others. Women and Science was a passionate defiance of the general belief that women are, by divine arrangement, incapable of original or creative mental work. Similarly, Great Inspirers was the story of the inspirational power of Beatrice as revealed in Dante, and of the holy women who labored with St. Jerome in Rome and Bethlehem. Both volumes are written with eloquence and fervor. Few men that ever lived had a more exalted conception of Christian womanhood. It was partly the result of a beautiful idealism that ran through all his life and work and thought and speech. It was partly a spiritual refinement which came to him from his intense love of Our Lady, and it was partly a flowering of his sensitive and delicate purity of mind. He shrank from any suggestion of coarseness of thought, word or behavior as from a blow. This strong man, who recoiled not from battle nor from labor, was as delicate-minded as a girl. But he went beyond that and believed in the power as well as the beauty of woman's mind. He has undoubtedly written greater books, but none more pleasing and inspiring than these two which deal with the soul of woman.

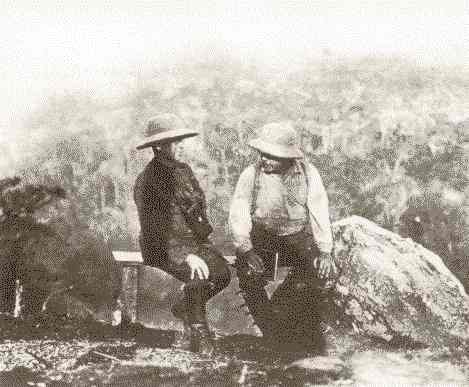

Another phase of his work yielded a cycle of books so different and so brilliant as to make one marvel they could come from the same mind. In 1906 Father Zahm, long familiar with Mexico, made his first trip to South America. Four years later, the Appletons published the first of a series of delightful and universally admired works from the pen of "Dr. H. J. Mozans." The general title of the trilogy was Following the Conquistadores, and the special titles were Up the Orinoco and Down the Magdalena (1910), Along the Andes and Down the Amazon (1912), and In South America's Southland (1916). American book reviewers were startled out of their usual perfunctory praise to exclamations of enthusiasm and rapture. The most frigid and parsimonious critics in England, with startling unanimity, used the words delightful, amazing, eloquent, erudite. The jaded palates of fastidious readers found a curiously piquant flavor in these books. Catholic editors and scholars wrote in superlative praise of this fresh discoverer of the continent of South America. But who was H. J. Mozans? One day Monsignor Joseph H. McMahon of New York, a scholar of taste and culture, wrote to the Appletons, asking for information about him for the purpose of preparing a literary appreciation of the books. The Appletons replied that the identity of the author must remain a secret by his own desire, but they courteously offered to send a photograph, and the Monsignor at once recognized the familiar features of his old friend. Father Zahm told me that in his youth he always signed his name Jno. S.{3} Zahm, and H. J. Mozans is merely a transliteration of that form.

What induced an author who had already attained world-wide fame for writings published under his own name, to relinquish that great advantage and challenge destiny afresh under a pseudonym? I happen to know that Father Zahm had sound personal reasons for wishing to keep his first journey to South America a secret for a time. But the explanation he himself gave was that these books, if presented frankly as the work of a priest, would not appeal so convincingly to the non- Catholic public, since they were so completely a glorification of the Church in South America, a vindication of the clergy through their works, and a sympathetic portrait of Catholic Latin-Americans. No one will question the wisdom of his course, as none can doubt the thoroughness of his success.

Here again, Father Zahm's scientific background did him excellent service. Not alone cathedrals, churches, convents, monasteries and schools, but the fauna and flora of the continent, the museums and scientific establishments, the intellectual movements among the clergy especially, the natural richness of mines and agriculture, and particularly the romance and heroism of missionaries and explorers, received full justice in his sparkling and flashing pages. Colonel Roosevelt, who wrote an enthusiastic introduction to the second volume of the trilogy, expresses astonishment at his scientific and historical knowledge, but especially at his amazing richness of literary allusion and poetic quotation from writers in many languages. In these three books, Father Zahm reached the perfect flowering of his literary style. His admirers had watched it grow from his earliest works, wherein it showed the unflavored dryness and correctness of a commercial document, into the habit of picturesque thinking and colorful phrasing, unto a richness and a pageantry of glorious words, a rhetorical costuming which clothed remote, abstract and scholarly things with beauty and splendor. From a purely literary point of view, these books marked the peak of his large and variegated life work. Seemingly as a pastime and between whiles, he published The Quest of El Dorado, in which he made complete and final disposition of one of the most fascinating and elusive themes connected with the earliest exploration days.

He was an enthusiastic student of Dante, and for more than thirty years it was one of his daily pieties to read a canto of the Divine Comedy in the original. He assembled at Notre Dame one of the three largest (probably the most rare and valuable) of the Dante libraries in America. He rummaged through every second-hand bookstore in Italy to make this collection, and one of his unfulfilled plans was to write the definitive Life of the great Florentine in English.

During the past six years, Father Zahm was occupied with a volume which he frequently assured me was to be his best performance. Though living intimately with him in community life, walking and talking with hiln every day, I never could learn from him just what was the subject of this great final effort. Nearly every day a large parcel of books would be delivered at his room from the Congressional Library, and I knew in a general way that he was writing on some such subject as the present-day status of Christians in Bible lands. The manuscript was ready for the publishers two months ago, but he wanted to visit the Levant again to freshen his eyes with local color and to verify intimate and important data and bring them up-to-date. He enjoyed a delightful and rejuvenating journey from Washington to Munich, visiting old friends and familiar haunts on the way. At Dresden, in a cold hotel, he contracted laryngitis, and shortly after he reached Munich, pneumonia set in. Father Zahm's health had been failing for three or four years. A famous specialist in New York had said his heart must have undergone a severe strain, and attributed it to the superhuman effort he made thirty-five years earlier in climbing the Mexican volcano, Popocatepetl. It had seldom, or perhaps never, been done by any traveler before, but that was only another reason why Father Zahm wanted to do it. And now, thirty five years later, Popocatepetl, with the relentlessness of material nature, was having his revenge. On November 10th, after only a few days of serious illness, Father Zahm passed away with all the rich consolations of that Faith which, throughout life, he had tenderly loved and to the defence of which he had dedicated his brilliant mind.

His personal characteristics were interesting. A spare hardy frame of middle stature had been disciplined to an iron toughness by a love of adventure, by travel in hard places and among primitive peoples. Few men ever squandered less energy on even the innocent "dissipations" of life. Though he spent many years in wine-drinking countries, he was almost ascetic in that matter, and he could never endure the smell of a pipe or cigar. He was the closest approach to pure intellect I have known in a reasonably long experience of great men. Despite his very quiet manner, he was a daring and courageous spirit, physically as well as mentally, and had in his life experienced some desperate situations in the course of travel. Few men of his period had so much energy, and none had more initiative. There was about him an innocent secretiveness regarding his works and his movements, and he liked to surprise his friends by unexpected achievements. His large, blue, innocent eyes bespoke the idealist. With strangers or others in whom his interest had not been aroused, he showed a sphinx-like reticence and a severely cold and polite manner; but as often happens, his frigid exterior was a sort of asbestos cloak to cover an unusually warm and affectionate nature. He easily forgave offences against himself, great or little, and in all ways he was remarkably charitable in speech and act. He loved to look at a baby, especially in his later years, and he had a beautiful sympathy with all young people. He never missed an opportunity of pouring his own burning love of scholarship and achievement into the hearts of seminarians and young priests. He himself was a great inspirer.

I have lived at Notre Dame University during nearly half the eighty years of its existence. I knew nearly all the great figures who -- in countless numbers, it seems to me -- have moved in and out of the campus during that long space. I regard Father Zahm as the greatest mind produced by the University in its long career, and perhaps the greatest man in all respects developed within the Congregation of the Holy Cross since its foundation. Maybe Father Zahm could not have laid the foundation of Notre Dame, but undoubtedly Father Sorin never could have built upon it as Father Zahm did.

To the rank and file of his brethren in the community, he was always a prophet as well as a leader. He was Vice-President of Notre Dame at twenty-five, and held the office nine years. He was Father Sorin's intimate friend, his trusted counselor; I saw him hold the venerable founder in his arms as he lay a-dying. In 1896 he was sent to Rome as Procurator-General of the community, and in cooperation with the mightiest leaders of the Church in America, he helped (sometimes not without peril to himself) to solve great problems and to direct large movements. While there he was asked to accept an appointment to a western bishopric, but he pleaded distaste and preoccupation with other work, and his plea was respected. Leo XIII., with whom he often talked freely, bestowed on him in 1895 the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. In 1898 he returned as Provincial of the community in the United States, and for eight years labored with such energy and success for its upbuilding and for the pursuit of higher studies as to inaugurate a new and brilliant era. At the end of his term as Provincial he retired to Holy Cross College in Washington, chiefly because he enjoyed there unparalleled library facilities. He never wasted an hour of time, and remained to the very end a miracle of industry, enthusiasm and zeal. His faith was of an apostolic simplicity and strength. He was scrupulous, especially in his later years, about religious exercises, and there was a beautiful note of tenderness in his personal piety. He knew and mingled with many of the greatest men of his period -- Popes, prelates, the lights of literature, the savants of science. But those to whom he most generously gave his heart and from whom he received the most beautiful affection and the strongest loyalty, were the religious brethren whom he inspired and guided by word and work for half a century.

1 What the Church Has Done for Science, and The Catholic Church and Modern Science. Notre Dame, Ind.: Ave Maria Co.

2 Americans learned how reasonable and necessary is the function of the Index during the recent War, when anything likely to weaken morale or provoke dissension was vigorously suppressed. The distinguished Dominican, Father Esser, an official of the Index, once told me, in speaking of Father Zahm, that among the functions of the Congregation Is the suppression of books calculated to arouse undue controversy among Catholics. The Italian translation of Evolution and Dogma seemed likely to do that, so Father Zahm. to use his own words, "voluntarily withdrew" it in 1900.

3 Stanislaus, an abandoned middle name.