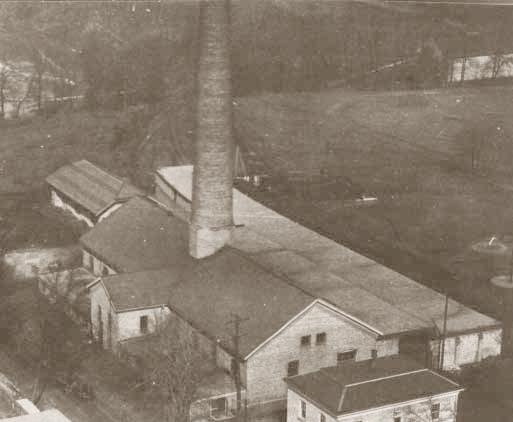

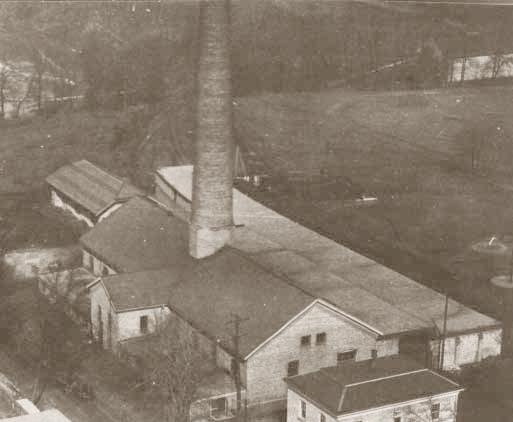

Boiler House and Electrical Plant

1899 Steam Plant

This year the number of entries was greater than ever. The pupils came the first days in such numbers that soon every spot was occupied, and beds had to be placed wherever they could be crowded in.

Then, laborers became so scarce that it was hard to find men to cut fire wood. The Council of Notre Dame suddenly found itself face to face with the almost impossible task of obtaining the amount of wood necessary for the winter, which had already set in.

After the most serious deliberation it was resolved to introduce steam heating as an escape out of the difficulty as had been done at St. Mary's. There was not a day to spare: it was November. The work was urged forward with all possible haste, and by Christmas the college was heated satisfactorily and economically, as it had not been done before.

The steam heating at St. Mary's a year earlier had much to do with the great reputation of the new academy. The council hoped that something of the kind would happen for the college, nor was it disappointed.

The advantages of this new system were not known until it was in full operation. Soon afterwards steam was introduced into the kitchen. It was everywhere considered a blessing, savings on an average twenty to twenty-five dollars a day. The administration took this occasion to raise the terms for board $20, and no one found fault.

The water is conveyed from the little lake you see gleaming beyond the trees into these two large boilers, whence it is conducted throughout the establishment, supplying also the water necessary for washing and other purposes. In the basement is the engine-room; above it a large and commodious bath-room, with a limited number of private closets, supplied with hot and cold water by pipes from the apparatus below. These are devoted to the use of the students of the University, during that season in which open air bathing is impracticable: and a perfect routine has been established, by which each student, in his turn, is enabled to enjoy the advantages of a bath as often as may be necessary. We need not say how much this advantage contributes to the happiness as well as to the hygienic welfare of the College. All who have ever tried it, we are sure, appreciate the comforts of a good bath.

[1899] Each of the buildings on the campus had had its own heating plant. This was expensive and wasteful. Together, Fathers Zahm and Morrissey determined on the erection of a central plant that would heat all the buildings. The plant was built on the site, approximately, of the present infirmary. It was considered quite an achievement. In fact, the builders sent a model of their work to the Paris exposition of 1900.

Until 1885 gasoline lamps had been the only source of artificial light in the buildings. When coal-gas lights came into use, the University planned to install them for, "although gasoline gives a nice, mild light, yet the experience of the past few years has been attended with many complaints, particularly because of the unsteady, variable nature of the light with its accompanying discomforts in reading and study." The University planned to have its own gas works in the rear of the College with a capacity of 15,000 cubic feet. The project, however, fell through when the contractors failed to keep their contract. This ultimately was no disappointment but rather "a source of pleasure to the authorities" because of the decision to introduce instead "the incandescent electric light" just developed by Edison. The first lights were installed in the corridors and study halls of the Main Building in September, 1885. The next month the crown on the statue of Our Lady on the Dome and the crescent at her feet were illuminated. So successful were the first lights that Father Walsh arranged to have nearly all the buildings lighted with electricity. The Edison Electric Light Company donated the dynamo, and the Armington and Sims Company gave the high-speed, low-pressure engine which supplied the power. The new electric light was "in every way a cleaner, brighter, and steadier illuminant than anything we have yet seen, and by reason of its brightness and absolute steadiness it is as easy on the eyes as sunlight itself." Almost equally wonderful as the light itself was its adaptability: "the lamps -- from two to six in a room -- are each suspended from the ceiling by two handsome, flexible, silk-covered wires, twisted together in the form of a cord, which supply the current. This arrangement allows a lamp to be brought to almost any position, thus securing the best effect in demonstration."

Before Edison had produced his incandescent lamp, several scientists in the seventies had produced good arc lights. At Notre Dame Father Zahm proposed lighting the grounds of the University with arc lights. It was one of those proposals which required success before being applauded. It was a real novelty when Zahm succeeded in October, 1881. For the student, it meant that he could take his recreation outside after supper. The Light Guards of Colonel Elmer Otis celebrated the occasion with a drill under the artificial lights.

It seems probable that Notre Dame was the first American college to have electric lights, if we can believe the claims of the New York Electrical Review. In March, 1887, a student of Bowdoin College wrote to the Review that Bowdoin was going to be the first college in America to be lighted by electricity. In reply, the Review pointed out that the arc light had been in use at Notre Dame since 1881 to illuminate the recreation grounds and that the incandescent lamp had been in use since 1885.